Understanding the Flight Paths That Shape a Nation’s Firepower

When India tested the BrahMos from a Sukhoi-30 in the Bay of Bengal, defence watchers cheered another leap in precision warfare. When it tested Agni-V, arcing into space before re-entering the atmosphere at twenty times the speed of sound, the applause was quieter, but heavier with strategic meaning. Both are missiles, both are Indian — and yet, the two might as well belong to different worlds.

Understanding why BrahMos is not Agni is not a technical exercise. It is a way to understand how India sees war, deterrence, and the idea of power itself.

The Physics That Defines Politics

The difference begins not in the warhead, but in the sky.

A ballistic missile like Agni is a sprinter. It burns bright and fast, shooting skyward on a column of fire, then coasts unpowered through space before diving back to Earth. Once its rocket stage cuts off, it is at the mercy of gravity and momentum — a projectile on a grand scale. It doesn’t fly; it falls gloriously.

A cruise missile, on the other hand, is a pilot. It stays inside the atmosphere, breathing the same air it flies through, guided by wings, fins, sensors, and algorithms. BrahMos, for instance, rides on a ramjet engine that keeps it powered and thinking all along the way. It doesn’t rise to space; it dances with the Earth’s surface — skimming oceans, slipping through valleys, hugging radar shadows.

This single difference — whether a missile flies or falls — creates two universes of warfare.

Agni: The Logic of Deterrence

The Agni series was born not for battlefields, but for balance. Its range, from a few hundred to over five thousand kilometres (currently deployed variant), is designed to reach capitals, not camps. Each test is not a rehearsal for war but a reminder of peace through fear — a message written in fire to every potential adversary: We can, therefore we need not.

The Agni family is the backbone of India’s strategic deterrent, but it did not begin there. It grew out of the early Prithvi programme of the 1980s — India’s first generation of ballistic missiles, short-ranged and liquid-fuelled, meant to prove that the country could master the basic science of controlled flight and re-entry. From that humble start came Agni-I, a theatre-range weapon; Agni-II and III, designed for regional reach; and the intercontinental Agni-IV and V, which now quietly hold the keys to India’s nuclear deterrent posture.

Supporting this family are systems like Prahaar and Shaurya, shorter-range and quasi-ballistic missiles that bridge tactical and strategic gaps. The sea-based K-series — K-15 Sagarika and K-4 — bring the same credibility beneath the waves, ensuring survivability through India’s nuclear triad.

What makes these systems remarkable is not just their reach, but their mobility and readiness. They can be launched from underground silos, rail and road canisters, or submerged platforms. Mounted on truck-borne launchers, they can move silently across the landscape, ready within minutes. A future evolution may even extend to ship-based surface systems.

A ballistic missile like Agni is not meant to be fired lightly. It is part of India’s credible minimum deterrence — a promise of restraint sustained by the certainty of response.

BrahMos: The Logic of Precision

If Agni is India’s roar, BrahMos is its whisper — the kind that unnerves more than it alarms.

Developed jointly with Russia, the BrahMos stands today as the world’s fastest operational cruise missile, travelling at around Mach 3 (currently deployed variant). It does not rely on sheer speed; it relies on amazing accuracy and intelligent manoeuvre — a missile that surprises the enemy by all means. It can be launched from ships, submarines, road-mobile batteries, or even fighter jets like the Su-30 MKI, striking targets hundreds of kilometres away with surgical precision. Where Agni’s flight is a parabola, BrahMos’s is a contour map — bending with the Earth, guided by reason rather than gravity.

Around it, India has cultivated a growing cruise-missile ecosystem. The indigenous Nirbhay, slower but longer-ranged, adds subsonic endurance to the supersonic BrahMos. The planned BrahMos-II, already under advanced development, aims to break the hypersonic barrier at Mach 6–7 — staying powered and thinking all the way to impact. Even the Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (HSTDV), tested by DRDO, feeds this lineage — a silent rehearsal for the future of powered hypersonic flight.

Together, these systems define India’s tactical precision strike capability, complementing the strategic deterrence of the Agni family. One family keeps the peace by threat; the other enforces it by precision.

Two Missiles, Two Philosophies

Together, Agni and BrahMos embody India’s dual personality in defence: the monk and the swordsman.

Agni represents restraint, patience, and strategic assurance — the cold comfort of knowing that India cannot be coerced.

BrahMos represents agility, innovation, and tactical confidence — the warm signal that India can act precisely, decisively, and fast.

To outsiders, they might look like different toys in the same arsenal. To strategists, they are opposite poles of national intent.

When India tests an Agni, it speaks to Beijing and Islamabad in the language of deterrence.

When it tests a BrahMos, it speaks to the world in the language of capability — of speed, accuracy, and destruction sharp enough to end a battle before it begins, and the confidence to sell that edge abroad.

The Science of Fear and Finesse

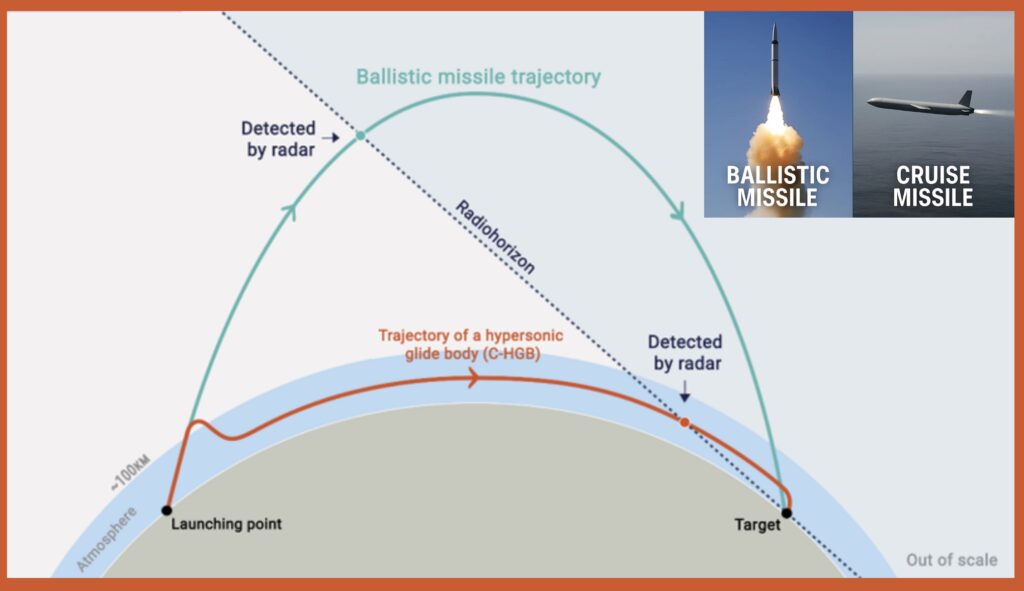

A ballistic missile achieves its speed by brute force — a massive rocket engine propelling it beyond the reach of air resistance. Once it reaches apogee, gravity does the rest. That descent, often above Mach 20, makes interception nearly impossible. But the trajectory is predictable — radar can track it the moment it rises. It’s a loud kind of invincibility.

A cruise missile like BrahMos trades raw speed for control. It thinks mid-flight, corrects its path, and adapts to moving targets. It is the scalpel to the ballistic sledgehammer. Because it stays low, radar sees it late; because it manoeuvres, defences struggle to guess where it will strike.

In the coming years, India’s next leap — the BrahMos-II — aims to erase even this distinction. Designed to reach Mach 6–7 using scramjet propulsion, it will be a true hypersonic cruise missile, staying powered all the way while flying faster than a bullet. That will be the moment when the line between “ballistic” and “cruise” finally blurs.

The Grey Zone of Tomorrow

Modern warfare no longer respects old boundaries. Scientists are building missiles that glide instead of fall, that think instead of obey, that manoeuvre in the edge of space where no airliner or satellite dares to fly. These are Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGVs) — and every major power is racing to master them.

India’s Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (HSTDV), tested by DRDO, is its first baby step into that race. It’s not yet a weapon — it’s a laboratory with wings — but it shows that India understands the future will belong to those who can stay hypersonic and controllable at once.

Why This Difference Matters

Understanding the difference between Agni and BrahMos isn’t just about aerodynamics — it’s about strategy.

Ballistic missiles shape deterrence; cruise missiles shape diplomacy.

A nation that builds both is one that can speak softly while carrying a very large stick.

Agni ensures India can survive a nuclear nightmare.

BrahMos ensures India can dominate a limited conflict without starting one.

In an age when wars are fought as much on television screens as in skies, the missile that is seen and the missile that is feared serve different masters.

Agni guards India’s existential peace.

BrahMos projects its practical power.

Both, in their own way, are instruments of restraint — one by promising devastation, the other by offering precision.

The Final Thought

The next time a plume of fire lifts off from Wheeler Island, or a flash of supersonic thunder ripples across the Bay of Bengal, remember that you are not just watching a missile test. You are watching India speak two dialects of the same strategic language — one ancient, one modern.

One arcs to the stars to remind adversaries what India can do.

The other hugs the sea to show the world what India will do.

That is why BrahMos is not Agni.

And that is why both matter — together.

Other Relevant Topics

India’s Indigenous Propulsion Leap: From 2.7–4.7 kN engines to the BrahMos hypersonic edge

US Missile Deal with Pakistan: Sparks regional debate and official clarifications

Readiness Redefined: India’s long march from arsenal to integration

India Successfully Test Fires Nuclear-Capable Agni-5: Extending strategic reach