PART – 1: The BBC and the Origin of Exploitative Documentary Making

Biscuits for the Lens — When Hunger Became a Headline

It was a crisp winter morning in Varanasi — the sacred city where rituals outlast empires. I was a schoolboy, likely in the 7th grade, trailing behind my elders when I stumbled upon a moment that would quietly plant the seed of lifelong scepticism toward Western media. On a crowded street near the ghats, I noticed two English photographers tossing biscuits — not into the hands of hungry children, but somewhere at distance — not to feed them, but to provoke them, to capture desperate expressions and chaotic movement.

At the time, I couldn’t comprehend what I was seeing. But years later, the pattern became clear that it wasn’t an isolated act of exploitation. It was part of a deeply embedded system of narrative control — one that began with the camera and extended far beyond the lens. The intent wasn’t to nourish; it was to provoke. The children lunged, collided, scrambled — and the shutters clicked in rapid succession, capturing not compassion, but chaos.

Framing India: Western Gaze, Narrative Control, and the Politics of Portrayal Series contains

PART – 1: The BBC and the Origin of Exploitative Documentary Making

PART – 2: Through the Western Lens: Slumdog Millionaire, and the Politics of Media Portrayal

PART – 3: Narratives of Convenience – Selling Suffering and Shaping Shame in the Global Media

PART – 4: BBC’s Fraught Relationship with India – Bans, Documentaries, and Debates

PART – 5: Slums and Shadows – Poverty in the West and Its Sanitised Cinematic Language [Status: In Progress]

PART – 6: Reclaiming the Lens – Toward Narrative Sovereignty and Self

From Observation to Orchestration

This incident was of the late 1970s, but the pattern had already begun decades earlier. A look through the archives of BBC documentaries and Western media from the 1960s to 1980s tells a consistent story — not about India, but about how the West chose to represent it. These documentaries did not depict a country in transformation or complexity. They were, instead, framed spectacles of deprivation.

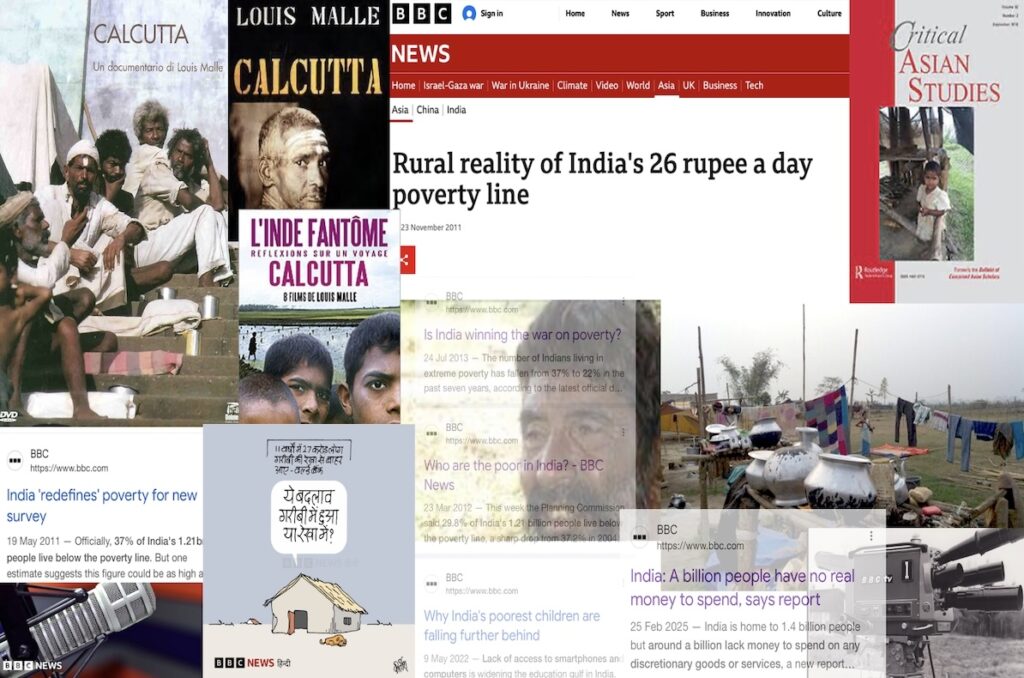

Titles like Calcutta (Louis Malle, 1969), India: The Search for Survival, and Hunger in India focused relentlessly on disease, slums, caste discrimination, famine, and squalor. The camera angle was literal – pointed downward. India, in these portrayals, was a land of suffering — always begging, always broken, always in need of saving. It was a view designed not just to inform, but to cement a certain moral and cultural hierarchy between the observer and the observed.

The Narrative Legacy: Permanent Backwardness

These documentaries were not neutral. They laid the foundation for a powerful Western perception of India as a land permanently trapped in its own misery — incapable of progress, dependent on aid, and defined by caste, chaos, and superstition. This narrative, repeated across decades and platforms, would later echo in mainstream cinema, such as in Slumdog Millionaire (2008), which I explore in the subsequent article.

What’s worth noting is that this wasn’t just storytelling — it was framing. These documentaries became part of the Western collective consciousness, and they shaped policy, diplomacy, journalism, and public opinion. India wasn’t seen as the world’s largest democracy, or a rising tech and space power. It was seen as the place where children ran barefoot in sewage, women starved silently, and temples coexisted with leprosy wards.

Intent vs. Impact: The Moral Mirage

Some might argue that these documentaries raised awareness. Perhaps the filmmakers believed they were fostering empathy. But that argument dissolves under the weight of consequences. The impact of these portrayals was not compassion — it was condescension. It turned India into a backdrop for Western virtue-signalling movements. It rewarded the storytellers while stripping dignity from the subjects.

This performative concern often ignored context, agency, and the actual voices of Indians. It flattened a civilisation of 5,000 years into a few crude stereotypes and made its poorest citizens the unwitting poster children of a global aid industrial complex.

There was no consent. There was no context. There was no compensation. What existed instead was moral theatre — India’s pain as a stage for Western applause.

“Throwing Biscuits”: A Deeper Symbolism

That memory from Varanasi has become more than a moment from childhood. It is a metaphor for the broader practice of dehumanisation disguised as documentation. The foreign photographers weren’t capturing poverty — they were manufacturing it. They weren’t feeding the hungry — they were feeding a narrative.

This is the uncomfortable truth: when the West point its camera at India, it too often captures what it wants to see — poverty without pride, hardship without hope, tradition without thought. What it omits is equally telling: India’s thriving middle class, its democratic institutions, its scientific progress, and its cultural and spiritual depth.

Has the BBC Changed? Partly. Superficially.

Yes, the BBC and some other media houses now have Indian correspondents, regional bureaus, and coverage of India’s tech sector, elections, and diaspora. But the mindset is still the same – selective emphasis continues. Stories on caste, communal violence, or state surveillance are often presented with little context or historical balance.

Even today, the positive developments are either underreported or framed with suspicion — an economic rise described as uneven, a political movement labelled majoritarian, a space launch viewed through the lens of hunger.

Even when India speaks for itself, the Western editorial scissors are never too far behind.

Conclusion: Who Holds the Camera — and Who Owns the Narrative?

This isn’t about censorship or denial. It’s about ownership — of narrative, dignity, and voice. The legacy of exploitative portrayal has real-world consequences. It affects how Indians are treated abroad, how development policies are shaped, how international aid is allocated, and how history is recorded.

The question is no longer whether poverty exists — it does, everywhere. The real question is: why is India’s poverty aestheticised while the West’s is sanitised? Why is an Indian slum a symbol of national shame while Skid Row in Los Angeles is a social problem?

It comes down to who tells the story, and for whom.

Today’s India is capable of telling its own story — through its writers, journalists, filmmakers, and thinkers. But the shadows of those early portrayals linger. The biscuits may no longer be thrown, but the gaze often remains the same.

It’s time we reclaim the lens — not to hide our flaws, but to frame our reality with the honesty, nuance, and self-respect we deserve.